After Oct. 7, the number of Shalhevet students asking whether they should remove parts of their college applications that disclosed their Jewish identity or Israel connections drastically increased, said Mr. Jordan Moss, Director of College Counseling, in an interview with the Boiling Point.

But seven months later, with anti-Israel encampments occupying colleges across the country, fear about the campuses themselves had overtaken other concerns about what’s euphemistically known by students as “the college process.”

“There’s just a lot of animosity towards Israel, to the point where many don’t even think that Israel should exist,” said Eva Brous-Light ‘22, a rising junior at Columbia University. “And embedded in that is very real antisemitism that’s been really challenging for a lot of Jewish students to contend with, and really painful at times.”

At UCLA, Alex Rubel ‘20 said that faculty and administration were doing nothing to support Jewish students on campus, and the responsibility of making sure they themselves were safe, as well as defending Israel and their identities, fell on the shoulders of the students themselves.

“For pretty much the entire school year,” Alex said, “we really had no choice but to respond to the anti-Israel – and often antisemitic – rhetoric that we’ve been seeing and experiencing.”

It was a rapid descent from how applying to college felt just a year ago, upending the already fraught process and turning it into something worse. Shalhevet seniors never made an effort to hide. The College Counseling Department encouraged keeping applications as they were pre-Oct. 7, and most did.

“You are submitting who you are,” Mr. Moss said. “You’re at a Modern Orthodox school, you aren’t going to hide being observant, attending Shalhevet. But we had a lot of those conversations.”

It also adjusted the way it described Shalhevet to universities.

“We changed our profile as soon as it happened,” Mr. Moss said. “We added a section that discussed how our community has been impacted by Oct. 7.”

After the Hamas attack, some students wrote more than they otherwise would have about Israel or their Jewish identity, and for some students the college counselors wrote more about Israel in their recommendation letters, he said.

But as the school year went on, it became impossible for Shalhevet seniors to think about college without imagining how they’d navigate being Jewish. Anti-Israel encampments and protests upturned and transformed their older friends’ experiences on campuses from the East to West coast and in between, in the most intense sequences of anti-Israel rhetoric any of them had ever experienced before.

Vivienne Schlussel ’23, a freshman at the University of Michigan, avoided the center of campus, which is where an encampment was located. It offered quicker routes to classes, but protestors occupied it for five weeks, until police cleared them on May 21.

At the USC, alumna Keira B. ‘23 – who did not want to use her full name because of “safety and privacy concerns” – said that in her classes she has heard other students say “Israel is committing genocide,” “Hollywood is Jewish,” and “anti-Zionism is not antisemitism.”

“I have professors who agree with these things,” said Keira. “I had to walk out of the class one time because I was so frustrated. And I was like, why am I forcing myself to sit through this conversation I am not allowed to partake in, because the moment I speak up I will be ostracized and judged?”

Jonathan Soroudi ‘23, also at USC, was angered by the protests.

“They claim they’re calling for peace and ceasefires while all of their chants are explicitly violent,” Jonathan said, offering examples like “There is only one solution, intifada revolution.”

Intifada is an Arabic word that means uprising, or shaking off, but often refers to violent uprisings against Israelis, coined during the First and Second Intifadas in 1987 and 2000. Some understand the word to mean committing acts of terrorism against Jews and Israel, while others understand it as a civil uprising.

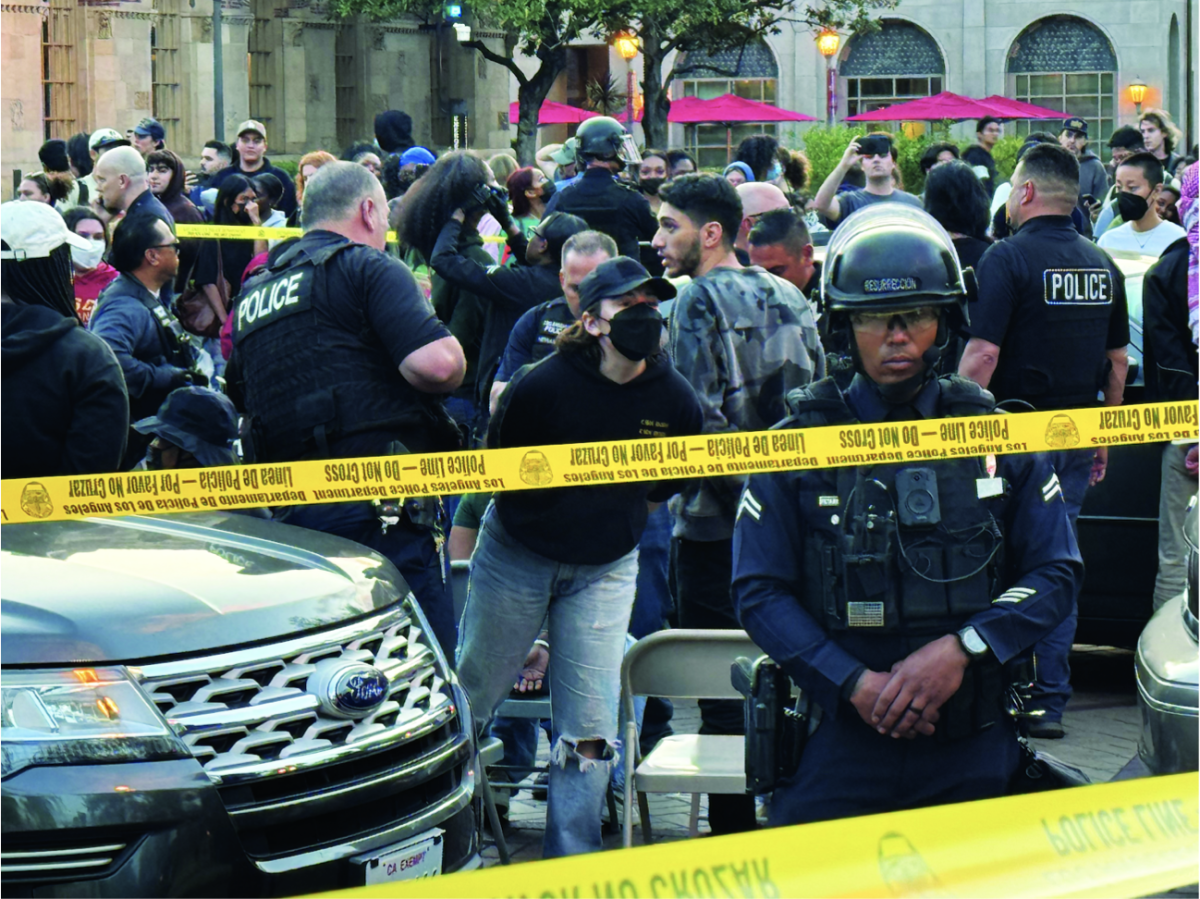

After police temporarily shut down the encampment at USC on April 24 – arresting 93 people – protestors rebuilt it. Eleven days later, on May 5, police cleared the encampment again, this time with no arrests, according to ABC News.

Jonathan himself took part in multiple pro-Israel counter-protests through the Chabad of USC. He described them as peaceful and the complete opposite of the encampments. He said that he and his Jewish friends there were constantly “harassed” for being Zionists and actively showing support for the State of Israel on campus.

Chabad ran a protest on the USC campus over Pesach where they set up tables and put an image of each hostage on a separate plate. Walking from the direction of the encampment, some students wearing keffiyehs seemed disturbed by the table, Jonathan said.

“A few of them were polite and wanted to have a conversation,” he said. “But the majority walked by in their keffiyehs eyeing you with a disgusted look on their face.”

Jonathan said he hadn’t expected an encampment to be built at USC, but he did expect protests after the university canceled the valedictorian’s commencement speech, which had been scheduled to be given by a Muslim American student, and then the entire graduation ceremony.

Like USC, universities across the country canceled commencement because of disruption and unrest.

A few miles away at UCLA, fifth-year student Sam Hirschhorn ‘18, who is graduating in a few weeks, went into the encampment there on May 4 to see what it looked like on the inside. A friend of Sam’s knew someone who was there and granted him access.

As reported by The Los Angeles Times, encampment members were preventing people from crossing Royce Quad, where it was located – quoting Eilon Presman, an Israeli UCLA student, who said he was blocked at a “checkpoint” because of being a Zionist.

Sam assumed the same would happen to him. He was in the encampment for only about 10 minutes, he said, reading the signs that were put up and walked around to see if the actual encampment affirmed the media’s perspective on the situation.

Inside he found spray-painted messages, a makeshift library, and various signs supporting the encampments’ cause.

“I think a lot of Jewish students have had fear and anger at these encampments,” said Sam. “Personally, I feel that I haven’t been scared at all.”

Sam said he blamed the media for giving too much attention to it, and as a result, stoking fear in students on campus. He said Jewish students’ fear was valid but was being used to paint all of the anti-Israel protesters as radical terrorism supporters.

On the night of May 1, according to the New York Times, pro-Israel counterprotesters at UCLA attempted to dismantle the barrier of the encampment, which the anti-Israel protestors then put back up, resulting in a flare-up of violence. Sam said the attack on was not a result of the people in the encampment attacking first, but of the pro-Israel side feeling anger and resentment toward the anti-Israel protestors.

This did not represent the views of most pro-Israel voices in Los Angeles, he said.

“That type of demonization of the other side is one of the reasons we got to this point,” said Sam.

He was also disappointed that the police did not do more to stop it.

“I think that the police were right to clear the encampment,” said Sam. “But just because they shouldn’t be there doesn’t mean that they don’t deserve protection from people attacking them.”

The encampment was taken down May 2.

At the University of Chicago, Kate Orlanski ‘21 said the protests were a “huge distraction,” and there have been times in class when she could not hear what her professor was saying because the chants coming from the encampments outside were so loud.

“You’re just trying to get to class and there are people wishing death upon your nation and your state,” Kate said.

One of the leaders of the encampments at UChicago was in one of Kate’s classes, and Kate and two other Jewish students were randomly assigned to be in a group with her. The person immediately asked to be removed from their group. Kate doesn’t know for sure whether it was because they were Jewish.

“I can’t say I think it was any other reason,” she said.

In Vivienne’s classes at Michigan, protestors interrupted lectures with chanting and marching.

A guest speaker came to give a lecture in one of her classes, and rallyists swarmed the hall where the class was held. Both the speaker and the professor of the class chanted along with the demonstrators, “Divest, don’t arrest,” a call for the university to divest its endowment from all corporations with connections to Israel, and for the police to not arrest the protestors for their actions.

During the first week when the encampments were up, Vivienne participated in a pre-Shabbat activity run by Chabad where they gave out challah to those walking by the center of campus. A student passing by “read on the package that it was spreading Jewish joy,” Vivienne said.

“Then she threw it back at us and said, ‘Take your genocidal bread,’” said Vivienne.

At Columbia, Eva too felt uncomfortable in her classes, particularly because she wasn’t able to ignore the encampments or avoid them.

“It was really frustrating because there was so much that I felt that these people didn’t understand and weren’t really willing to understand,” Eva said. “I wasn’t able to just be a student and go to my history class.”

She took most of her finals as take-home exams or essays, she said, and her last two weeks of classes were hybrid learning because of all the disruption on campus.

For the most part, she said, did not feel physically unsafe on campus. Kate felt similarly but said the encampments had “decreased the general feeling of safety on campus.”

Columbia’s protests started right after Oct. 7, Eva said, but were nothing like the encampments. The most disruptive and aggressive protests were when the rallyists occupied Hamilton Hall.

The protesters barricaded the doors and smashed the windows of the building, Eva said, then moved from the main lawn in front of Low Library into the building.

“When the encampments were up, I went to classes,” she said. “But I remember sitting in class – the classroom was rattling because you could hear everyone yelling from the lawn, just screaming. And this was the day of the mass arrest, so they were obviously very upset about it, they were just yelling.

“It was almost impossible to pay attention to the professor. My lecture was nearly empty because even if you weren’t involved in the protests you were so interested in what was happening…

“Everyone kind of made school a second priority.”

Many Jewish students at Columbia signed a letter in the last two months authored by the heads of different pro-Israel groups on campus.

Eva, one of at least three Shalhevet alumni who signed it, said the purpose of the letter was to inform the larger Columbia community that the Jewish students on campus, despite harsh opposition, still staunchly support Israel.

The letter’s intent was also to “explain to people who don’t understand what Zionism is, why it’s important to us and why we value it as Jewish students,” Eva said.

More than 540 students signed it.

“Many of us sit next to you in class,” the letter reads. “We are your lab partners, your study buddies, your peers, and your friends…

“Most of us did not choose to be political activists. We do not bang on drums and chant catchy slogans. We are average students, just trying to make it through finals much like the rest of you. Those who demonize us under the cloak of anti-Zionism forced us into our activism and forced us to publicly defend our Jewish identities.

“We proudly believe in the Jewish People’s right to self-determination in our historic homeland as a fundamental tenet of our Jewish identity. Contrary to what many have tried to sell you – no, Judaism cannot be separated from Israel. Zionism is, simply put, the manifestation of that belief.”

She said Columbia’s Jewish community is stronger than ever and she’s proud to be a part of it.

“I don’t think the Jewish community should recede from these institutions,” Eva said. “They need us, and they need our perspectives…. We shouldn’t let them scare us out of these spaces because our voices are needed.”

Back in March – just two months ago – three out of four Shalhevet seniors interviewed by the Boiling Point had kept their applications the same, and also maintained their plans for which schools to attend. What changed for all four, however, was their perspective and approach to their post-Shalhevet plans.

For Datya Kurzban and Zion Schlussel, campus Jewish communities became a higher priority. In Datya’s case, last fall that meant speaking to Jewish students about the atmosphere, and university administrators about their plans to help combat antisemitism.

“It ecame more important to me to see how the schools were reacting,” Datya said.

For senior Maayan Mazar, however, “everything changed.”

“So many of the schools that were top priority on my list are just seeing such horrendous antisemitism,” Maayan said in March.

“I was just talking to students there, they weren’t feeling safe,” she said. “And I just knew that yes, these were prestigious institutions, but I just wouldn’t feel like I could be a proud Jew going there. Even though they were prestigious I took them off my list.”

Maayan initially planned to apply to 13 schools, including the University of Pennsylvania’s nursing program. Ultimately she only applied to seven – excluding Penn.

This story was originally published in The Boiling Point, Shalhevet High School, on June 3, 2024.